Toxic risk under a microscope

Dozens of examples of the toxic risk faced by Australians illustrate why we all need to take heed of the historic property contamination.

DOZENS of examples of the toxic risk faced by Australians illustrate why we all need to take heed of the historic property contamination.

Australian Conveyancer unpacks a growing list of worrying case studies that have surfaced over the past two decades.

Ground and surface water

Sediments in Lake Macquarie, an estuary near Newcastle, have some of Australia’s highest concentrations of contamination courtesy of industrial activity in the area since the 1890s.

The Botany Bay Groundwater Plume, a legacy of the old ICI site which manufactured paints, plastics and industrial chemicals, is one of the country’s most severe cases of groundwater pollution. Some chemical levels detected in the aquifer are 5,000 times over safe levels. The cleanup effort is expected to last decades.

Department Victoria developed Melbourne’s Cairnlea Housing Estate on the old Albion Explosives Factory site, which produced explosives and munitions for the Department of Defence which affected soil and groundwater. Some contamination remains but the EPA has cleared residential areas with a certificate of environmental audit.

Nine suburbs of Adelaide are affected by groundwater contamination, the legacy of industrial solvents and degreasers. The EPA SA has established a Groundwater Prohibition Area (GPA), banning the use of bore water for drinking, showering or irrigation to mitigate health risks.

In 2019 the NSW EPA cautioned residents to limit their consumption of fish caught in the Shoalhaven River after up to 100,000 litres of PFAS-contaminated wastewater were allegedly discharged into the Shoalhaven sewer system and river.

Landfill sites

In 2023 owners of 50 bush blocks in Busselton in WA’s South West were told the groundwater on their properties is poisoned by toxic sludge from the town’s old landfill site. The owners must now add the contaminated land status to their title deeds.

In 2020 the NSW EPA declared sports ground Foxglove Oval in Sydney’s Mt Colah a “significantly contaminate site” due to its previous use as a landfill. Monitoring of two homes adjacent to the oval showed elevated levels of landfill gas. Work to reduce off-site migration of ground gas was completed last year.

A secret dumping ground containing building rubble, including asbestos, was discovered in Wheeny Creek in the Hawkesbury region. This year the Sydney Morning Herald reported the site is still not remediated – four years after its discovery – and is now leaking contaminated waste into a protected wetland.

Residents in Ipswich are concerned emissions from the commercial Swanbank Landfill site are affecting their health. Despite measures to mitigate contamination – including fully lined cells and a leachate management system – the community is still concerned about health impacts, particularly from hydrogen sulphide gas.

In 2008, a housing estate planned for land near a former tip in Ballarat’s Black Hill was halted when large amounts of waste and landfill gas were found. Ballarat Council was forced to buy the contaminated land back from the developer because the site was unsuitable for residential development.

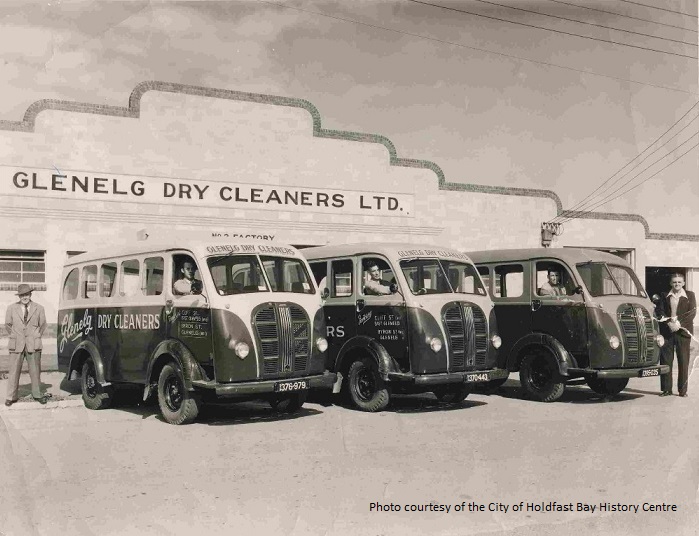

Dry cleaners

Prior to 1991 dry cleaners in Australia were unregulated with many historical sites left unchecked and capable of leaching toxic solvents, like Perchloroethylene (PERC) and Trichloroethene (TCE), into surrounding soil and waterways.

Linked to increased cancer risks, PERC can also lead to air pollution through volatile organic compounds (VOC) emissions. While exposure to the potentially carcinogenic TCE can happen through air, water, or skin contact, and can affect a person’s central nervous system.

In 2016 the Department of Veterans’ Affairs formally recognised exposure to TCE as a cause of Navy veteran Keith Bailey’s Parkinson’s disease. Mr Bailey had been exposed to the chemical for up to 12 hours a day in his job cleaning motor parts onboard Navy ships.

Across the country, Lotsearch has identified around 5000 sites which have the potential to be affected by historical dry cleaner activities and could pose a risk to health and land values.

US-based company EnviroForensics says PERC is one of the more expensive contaminants to remedy. And the cleanup of a contaminated dry cleaning site is often more complicated than a cleanup of a contaminated petrol station because petroleum products will float on water while PERC is heavier than water and will sink down past groundwater tables until it hits bedrock.

“When a release of PERC to the ground occurs and it reaches down to the groundwater table, it will continue to sink until it hits a layer of dense material, like clay,” says the environmental consultancy group. “It will sit there and continue to dissolve for a long time, which can cause a long groundwater contamination plume.”

According to SA Health, when these long-lasting chemicals like PERC and TCE contaminate soil and water supplies, they can spread far from the original source of contamination and be difficult to remediate.

“In some cases contaminated groundwater and soil vapour can move off industrial sites and may be present under residential properties,” the government department states.

This was the case in 2003 in Brunswick, Victoria, when buyers of 49 recently completed units, located next door to a former Spotless dry cleaners, could not move into their apartments after the EPA discovered soil contamination. The developer was unaware the site was contaminated and had to cancel the sales and pay the construction costs of the building, forcing them into administration. In 2007, a judge ordered Spotless to pay $7million for remediation of the site.

Service Stations

Crisscrossing the nation, underground petroleum storage systems (UPSS) are one of the most common sources of both land and groundwater contamination in Australia – and pose a real danger of contaminating neighbouring land.

According to the WA Department of Water, service stations can pose contamination risks to water resources through the “leakage of fuel, and the spillage of engine coolant, hydraulic fluid, lubricants and solvents, along with the inappropriate containment or disposal of wastes such as car parts, batteries and tyres”.

The Victorian EPA says: “UPSS have the potential to leak, leading to expensive cleanup costs, damage to the environment and risks to human health.”

In NSW, with more than 7,000 historic sites and around 2,500 modern sites (Lotsearch data), leaks from underground fuel tanks and pipework at service stations are a common source of soil and groundwater contamination, according to the EPA.

“Service stations make up the single largest sector of contaminated sites in NSW,” says the state’s environmental agency, “and proper assessment of service station sites is crucial to making sure human health and the environment are protected from potential impacts of contamination.

“Of the many thousands of decommissioned service station sites in NSW, there may be some with elevated concentrations of petroleum product in soil and groundwater.”

Using old telephone books to map the locations of historic service stations, Lotsearch has identified more than 22,000 sites where service stations once operated countrywide, along with nearly 7,000 modern sites. (SEE 4.3 Lotsearch Analysis FOR GRAPH)

For the owners of affected neighbouring properties, financial compensation can be difficult to come by. In August this year, David Harris, the member for Wyong in NSW, called on the owners of a Kanwal service station, which was declared “significantly contaminated” by the EPA in 2018, to shut down until petrol storage tanks contaminating the site and nearby properties were fixed.

Harris said a cleanup order, issued by the NSW EPA in 2020, had been ignored by the service station owner’s Zoya Investments P/L, and more than 3,000 litres of petrol could have leaked from the underground storage tanks and into adjacent properties.

One neighbouring property owner is owed $8.45million in damages from the service station proprietors, who, according to Harris, declared no assets in April 2024 “to avoid responsibility to clean up the petrol station site”.

Gasworks

Beginning in the late 1800s, gasworks were built to produce town gas for heating, lighting and cooking with extensive sites located in the heart of our growing cities like Sydney’s Barangaroo, the South Melbourne Gasworks and the Newstead Gasworks in Brisbane.

In NSW, the state’s EPA says the operation of over 60 former gasworks sites throughout the state has left a legacy of soil and groundwater contamination which should be addressed before the land is reused.

“Some of these contaminants are carcinogenic to humans and toxic to aquatic ecosystems and so may pose a risk to human health and the environment,” says the NSW EPA. “As a result, many former gasworks sites will require remediation before they will be suitable for sensitive land uses, such as housing.”

The NSW Department of Environment and Conservation says gasworks were typically located “near waterways or train lines for easy delivery of coal. They were often also close to the centre of the city”.

In Melbourne, the former Fitzroy Gasworks – just 2km from the CBD – was known as one of the city’s most contaminated sites. But, after four years of rehabilitation, completed in 2022, the land is now slated for development of 1,200 apartments.

Risk-mapping expert Howard Waldron from Lotsearch says, like most former gasworks, the Barangaroo site in Sydney proved challenging for the developers of Crown Casino and the surrounding skyscrapers.

“Where you have a contamination problem it may not necessarily be a risk until that contamination issue is exposed, like in the case of Barangaroo,” says Waldron of the site once home to the former Australian Gas Light Company.

“It was a very old facility and they buried the tar-like material under the ground and capped it with concrete. So the material was there and very contaminated but it wasn’t exposed to the general public in any way.

“But as soon as they started to redevelop and build the casino and all those towers, they technically were going to have to cut through the concrete and expose the contamination. And, when that happens, then there is a source pathway and receptors in play and that’s when consultants are needed to determine if there is an actual risk.”

PFAS

Known as ‘forever chemicals’ PFAS have been in the news for all the wrong reasons in recent months with the detection of elevated concentrations of these potentially toxic substances found in Sydney’s water catchments.

The Medlow Dam in the Blue Mountains, which provides water to 41,000 residents, was closed as a ‘precautionary measure’ after tests last month (August) revealed elevated levels of PFOA, one of the forever chemicals.

Described as the ‘next asbestos’ PFAS – a group of nearly 4,700 synthetic chemicals – have been used in a variety of products including non-stick cookware, Scotchgard, fire-fighting foam, sunscreens, fitness wear and cosmetics. They are bio-accumulative, which means they accumulate over time in living organisms including humans.

In Australia, historical use of fire-fighting foam has resulted in increased levels of PFAS being found at sites including defence bases and airports. And, in May 2023, the Commonwealth settled a $132.7 million class action over PFAS contamination affecting 30,000 residents across seven sites around Australia, located close to defence bases.

Lotsearch has mapped the PFAS investigation areas related to these defence sites and airports, affecting over 45,000 lots, and includes this information in their reports.

According to the Australian Government PFAS Taskforce, the properties that make some PFAS chemicals useful in many industrial applications and particularly in fire-fighting foams, are the same properties which make them problematic in the environment.

“The PFAS of greatest concern are highly mobile in water, which means they travel long distances from their source-point; they do not fully break down naturally in the environment; and they are toxic to a range of animals,” says the taskforce.

“While understanding about the human health effects of long-term PFAS exposure is still developing, there is global concern about the persistence and mobility of these chemicals in the environment.

“Many countries have discontinued, or are progressively phasing out, their use. The Australian Government has worked since 2002 to reduce the use of certain PFAS.”

Environmental group Friends of the Earth says the Australian Government needs to do more to protect citizens.

“PFAS chemicals have been linked to a number of diseases,” says the group, “yet the Australian Government stubbornly refuses to end the use of PFAS chemicals in Australia, even after they have been banned overseas.”